Today was the day of the 40th Test on Proficiency in Korean, which I took at the University of Washington. Two or three months ago, I took three previous exams at home—TOPIKs 35, 36, and 37—and scored well enough to be classified as a Level 2 Korean language user ("high beginner"). The test today was much harder than those previous tests, and not only because of the time limit, which wasn't an issue for the tests I took at home. I had to skip many questions because I just couldn't find a way into them, and then I ran out of time to go back and give them another try.

I don't see how it's possible I'll enter the ranks of the Level 2s. Not until TOPIK 42 (mid-October, 2015) at the earliest. (TOPIK 41 will be given only in Korea.) It is pretty disappointing to be judged only a "low beginner" after a year and a half of study. I think my Korean is more serviceable than this test suggests, partly because the listening portion of the TOPIK was really hard for me, as I knew it would be. (In the previous tests I took at home, there were many listening questions I could only really guess on. In today's test, a good half of the listening questions just left me sitting there with no clue.) In my civilian (non-test taking) life, when I'm using Korean with my teacher or with my Korean-speaking friends, I do much better than you'd expect from a "low beginner." Oh well.

A score of 80 is needed to rank as Level 1, 140 to rank as Level 2. In the tests I took on my own, I scored 150, 155, and 160. I'm guessing I got a score no higher than 100 on today's test. (Results are scheduled to be posted June 16.)

In my testing room, I was the oldest testee by far. The second-oldest test-taker could have been 25 years younger than me. Most of the testees were kids around 10–12. All but two test-takers were Korean or Korean-American, at least some of whom spoke Korean at home. So I was a real anomaly: a middle-aged guy not immersed in Korean. Maybe considering that, I did fine.

TOPIK 42 (and Level 2) or bust!

Message to self: Next time, wear a watch to keep track of time and pace yourself. And study more vocab in the weeks leading up to the test.

Thoughts about words, capital-L Language, little-L languages, and other junk.

Saturday, April 25, 2015

Wednesday, April 22, 2015

English Etymology: a rule of thumb

If someone tells you that some English word started its life as an acronym (a pronounceable series of initials or other word pieces), nod politely and be on your way. It's probably not true. For every laser (from "light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation") and scuba ("self-contained underwater breathing apparatus"), there is a whole drawerful of cruds (not actually from "Chalk River unidentified deposits"), fucks (not from "fornication under consent of the king" or "for unlawful carnal knowledge"), and KISSes (the band's name is not an acronym for "Knights in Satan's Service").

Acronyms are super, useful, and superuseful. They're just not the English language's favorite means of coining words. Some languages employ this technique very productively, like Russian, which loves acronyms. But not English. Sometimes this means colorful stories about words' histories are false, and the world becomes just that much less magical. But this is forever the cost of truth.

Wikipedia has a brief list of other not-really-acronyms. Memorize them all. Annoy your friends.

Acronyms are super, useful, and superuseful. They're just not the English language's favorite means of coining words. Some languages employ this technique very productively, like Russian, which loves acronyms. But not English. Sometimes this means colorful stories about words' histories are false, and the world becomes just that much less magical. But this is forever the cost of truth.

Wikipedia has a brief list of other not-really-acronyms. Memorize them all. Annoy your friends.

Monday, April 20, 2015

Korean Mnemonics 3: Monday and Tuesday

I have spent countless months unable to keep 월요일 (weolyoil "Monday") and 화요일 (hwayoil "Tuesday") straight.

Ignore that last part of the word—the 요일, found in all names of the days of the week—and you're left with 월 (weol) and 화 (hwa). The shapes of the vowels can help, maybe (just like in Korean Mnemonics 1)? In the word for Monday, the vowel ㅓ points backward, as though toward the weekend that just ended. In the word for Tuesday, the vowel ㅏ points ahead toward the next weekend.

I think I'm going crazy.

I admit it: this is totally strained, and remembering this could end up being as hard as just remembering which word is which. But I need this! I have looked up Monday and Tuesday so many times. Never again!

Isn't it funny how the arbitrariness of words—the essentially random connection between word and referent—seems to vanish when it's your own language? Of course the English words Monday and Tuesday are easy to keep straight: Monday could only mean, you know, Monday, and Tuesday just sounds so... Tuesday. But when you're staring down the barrel of a foreign lexicon, everything seems like a slippery mishmash with nothing to grab hold of. So I'm reaching for anything that floats, even if it's some cockamamie story about vowels pointing to weekends.

Bonus for English language learners: I just thought of something. If you're having trouble with Monday and Tuesday, all you have to do is remember that Monday is the one-day, and Tuesday is the two-day.

Ignore that last part of the word—the 요일, found in all names of the days of the week—and you're left with 월 (weol) and 화 (hwa). The shapes of the vowels can help, maybe (just like in Korean Mnemonics 1)? In the word for Monday, the vowel ㅓ points backward, as though toward the weekend that just ended. In the word for Tuesday, the vowel ㅏ points ahead toward the next weekend.

I think I'm going crazy.

I admit it: this is totally strained, and remembering this could end up being as hard as just remembering which word is which. But I need this! I have looked up Monday and Tuesday so many times. Never again!

Isn't it funny how the arbitrariness of words—the essentially random connection between word and referent—seems to vanish when it's your own language? Of course the English words Monday and Tuesday are easy to keep straight: Monday could only mean, you know, Monday, and Tuesday just sounds so... Tuesday. But when you're staring down the barrel of a foreign lexicon, everything seems like a slippery mishmash with nothing to grab hold of. So I'm reaching for anything that floats, even if it's some cockamamie story about vowels pointing to weekends.

Bonus for English language learners: I just thought of something. If you're having trouble with Monday and Tuesday, all you have to do is remember that Monday is the one-day, and Tuesday is the two-day.

What Does English Sound Like?

I have no idea. To me, English sounds like... nothing. It's the barest film between reality and the words used to describe and convey it. I often ask English language learners what English sounds like to them.

The answers haven't been too satisfying. It's kind of a stupid question. And it can be pretty slippery and impressionistic. Still, I've been told that English speakers sound like they're chewing gum, that English sounds "too smooth," and that English speakers tend to sound very active and enthusiastic.

I wish I could exist as someone with no knowledge of English for a little while, just so I could hear it with innocent ears, just hear the sounds of English. Just hear the music—and not the math—of the language.

If you are a non-native English speaker, tell me, please: What does English sound like to you?

The answers haven't been too satisfying. It's kind of a stupid question. And it can be pretty slippery and impressionistic. Still, I've been told that English speakers sound like they're chewing gum, that English sounds "too smooth," and that English speakers tend to sound very active and enthusiastic.

I wish I could exist as someone with no knowledge of English for a little while, just so I could hear it with innocent ears, just hear the sounds of English. Just hear the music—and not the math—of the language.

If you are a non-native English speaker, tell me, please: What does English sound like to you?

Tuesday, April 14, 2015

Korean Mnemonics 2: uncle and cousin

Words that look alike and mean similar things are especially hard to keep straight. And that's the case with 삼촌 (samchon "uncle") and 사촌 (sachon "cousin"). I don't know if this has anything to do with the etymology of the words, but the first syllables (삼 and 사) mean "3" and "4," respectively, in the so-called Sino-Korean number series.

So just remember that 삼촌 (3-촌) comes before 사촌 (4-촌), just as uncles come before cousins. They're born first, and deserve more... respect... as elders...?

Whatever works.

Update: I just brought this up with my teacher, who tells me that my trick actually is based on the etymology of the words. In addition to 3-촌 (uncle) and 4-촌 (cousin), there is also 5-촌 (오촌, ocheon "parent's sibling's child; that is, second cousin") and beyond! So while English has a system of increasing distance (2nd, 3rd, 4th, once removed, etc.), Korean uses a system of addition, where family relationships are tallied up.

So just remember that 삼촌 (3-촌) comes before 사촌 (4-촌), just as uncles come before cousins. They're born first, and deserve more... respect... as elders...?

Whatever works.

Update: I just brought this up with my teacher, who tells me that my trick actually is based on the etymology of the words. In addition to 3-촌 (uncle) and 4-촌 (cousin), there is also 5-촌 (오촌, ocheon "parent's sibling's child; that is, second cousin") and beyond! So while English has a system of increasing distance (2nd, 3rd, 4th, once removed, etc.), Korean uses a system of addition, where family relationships are tallied up.

Monday, April 13, 2015

Favorite Words 2: place names

I don't know if these are good places, but these are good words. It's easy to think that someplace named so well must be worth visiting. The words open up grand landscapes, each with its own echoes and imaginable, if hazy, history.

- Zimbabwe

- Kyzyl-Kym

- Zanzibar

- Coquitlam

- Tegucigalpa

Learning Korean 2

This is the grammar I've been working on lately:

1. The honorific suffix: -으시, which I would like to call the horrific suffix, because it's confusing and complicated.

This is my first systematic exposure to the honorific form. Before digging into this chapter, I had really only seen the honorific in memorized-as-a-whole forms, like 주셔서 감사합니다 (jusyeoseo kamsamnida "thank you for") or polite imperatives like 앉으세요 (anjeuseyo "please have a seat"). But now I see where those forms come from, which is nice. But understanding the ways 시 changes form, having to remember whether the construction in question calls for the bare stem or the 어/아 form, and trying to wrap my mind around the whole honorific system make using the honorific a challenge. I'll talk about Korean's honorific and politeness axes in a later post.

2. The so-called long negative: -지 않다

어제 아파서 아무것도 먹지않았어요. ("Because I was sick yestersay, I didn't eat anything.")

3. The "obviously, as you know" construction: -잖다

A. 잘 한국어를 하고 있어요! ("You're speaking Korean well!")

B. 저는 열심히 공부하잖아요. ("Well, as you know, I do study hard.")

4. The "worth doing/doable/understandable that" construction: -을 만하다

오늘은 저를 학교에 데리고 갈 만해요? ("Can you take me to school today?" "Is it doable to take me to school today?") Note that this is different from 오늘은 저를 학교에 데리고 갈 수 있어요? ("Are you able to take me to school today?") and 오늘은 저를 학교에 데리고 갈래요? ("How about taking me to school today?"), which is different from 오늘은 저를 학교에 데리고 가고 싶어요? ("Do you want to take me to school today?).

5. The "nothing but/no more than" construction: 밖에 안/못

저는 고양이들밖에 기르고 싶지않아요. ("I don't want to raise anything other than cats.") Remember that 밖 means "outside or outside of," and this construction is easy. I don't want to raise anything outside of (or anything beyond) cats.

6. About or concerning: -에 대해(서) / -에 관해(서)

우리 돈에 대해서 생각합시다. ("Let's think about money.")

1. The honorific suffix: -으시, which I would like to call the horrific suffix, because it's confusing and complicated.

This is my first systematic exposure to the honorific form. Before digging into this chapter, I had really only seen the honorific in memorized-as-a-whole forms, like 주셔서 감사합니다 (jusyeoseo kamsamnida "thank you for") or polite imperatives like 앉으세요 (anjeuseyo "please have a seat"). But now I see where those forms come from, which is nice. But understanding the ways 시 changes form, having to remember whether the construction in question calls for the bare stem or the 어/아 form, and trying to wrap my mind around the whole honorific system make using the honorific a challenge. I'll talk about Korean's honorific and politeness axes in a later post.

2. The so-called long negative: -지 않다

어제 아파서 아무것도 먹지않았어요. ("Because I was sick yestersay, I didn't eat anything.")

3. The "obviously, as you know" construction: -잖다

A. 잘 한국어를 하고 있어요! ("You're speaking Korean well!")

B. 저는 열심히 공부하잖아요. ("Well, as you know, I do study hard.")

4. The "worth doing/doable/understandable that" construction: -을 만하다

오늘은 저를 학교에 데리고 갈 만해요? ("Can you take me to school today?" "Is it doable to take me to school today?") Note that this is different from 오늘은 저를 학교에 데리고 갈 수 있어요? ("Are you able to take me to school today?") and 오늘은 저를 학교에 데리고 갈래요? ("How about taking me to school today?"), which is different from 오늘은 저를 학교에 데리고 가고 싶어요? ("Do you want to take me to school today?).

5. The "nothing but/no more than" construction: 밖에 안/못

저는 고양이들밖에 기르고 싶지않아요. ("I don't want to raise anything other than cats.") Remember that 밖 means "outside or outside of," and this construction is easy. I don't want to raise anything outside of (or anything beyond) cats.

6. About or concerning: -에 대해(서) / -에 관해(서)

우리 돈에 대해서 생각합시다. ("Let's think about money.")

Sunday, April 12, 2015

NPR and the Flap

Ed. note: I started writing this fifteen years ago, and I’ve been thinking about it ever since. The examples below of on-air speech are from 2000 and 2001.

Something about NPR has been driving me crazy for a long time now. At first, I couldn't identify it. But then my training in linguistics kicked in, and it all made sense. Many NPR commentators and announcers consistently exhibit affected speech patterns, and that's what I want to tell you about. But before I do that—and in order to make my rant enlightening—I need to go into some basic facts about phonology. It's my hope that the following lesson will give my rant more weight, and explain clearly why and how NPR made me nuts.

Flapping

American English has, as a part of its phonological system (its system of speech sounds), a rule concerning the sound called a flap. What is spelled "tt" in the word butter is pronounced as a flap. What is spelled "t" in the word metal is pronounced as a flap, also. We spell it with t's, but we don't pronounce it with t's. No American English speaker in his or her right mind pronounces these words as though there's a "hard" t in them. When I say "hard," I mean what linguists would call an aspirated t. That is, a t produced with a tiny puff of breath following the release of the sound. In a word like top, the t is aspirated. But in stop, the t is unaspirated. Say them. You'll see what I mean. (Introductory phonetics textbooks usually tell people to hold their hands in front of their mouths to feel the difference between the t in top and the t in stop. It’s more noticeable doing this with spot and pot to see the difference between the unaspirated and the aspirated p.) When I say, "in this case, t is aspirated, but in this other case, it's not," I don't mean there's some rule in a book that says American English speakers have to do this in order to speak "correctly." No, this is just one of many, many things Americans know about their language without even knowing that they know it. No one taught it to them any more than they were explicitly instructed to put adjectives before nouns, or to pronounce the plural of dog with a z sound at the end and the plural of cat with an s sound.

Okay, so far, so good. American English has flaps. Not only that, we have a rule that governs when to flap. In other words, flapping is systematic. Predictable. You could even say "grammatical." Look at the word markets, as in "The markets were crowded today." That t in market is a regular old t. But what happens when market gets a different ending attached to it, like -ing? What about the word marketing? What happens to the t in that case? It gets turned into a flap. I'll write that flap sound with a D. In other words, marketing is actually pronounced [markeDing], with a flap where the spelling of "marketing" might lead you to expect the t sound. Sure, in jolly old England, they might pronounce it [marketing], but this is America. Let's be clear here. In jolly old, they'll actually pronounce the t in marketing in its aspirated form. (This is one of the main things you should do if you're trying to sound like the British upper crust: aspirate your t's.) I'll write that aspirated t like so: T. (Hey, this is even present in the word British. We Americans say [briDish], but over there, they call themselves [briTish].) To sum up, in America, it's [markeDing] (and [buDer] for butter), while in England it's [markeTing] (and [buTer]—or more like [buTa], but that's a different issue). By the way, these bracketed forms aren't "official" phonetic representations of the words in question. I'm greatly simplifying things, so I can make my case about flapping.

What is a flap, anyway? Phonologically, is it just a kind of t or d? Well, no, it's not. Might be simpler if it was, but it's not, really. Even though flaps get spelled with t's and d's in English—and I'm using [D] to represent them here—they're actually a different sort of sound. If you were to look at a sound spectrogram of a flap—a depiction of the acoustic energy involved in the transmission of a flap—you'd see that flaps have more in common with sounds like r and l than they do with t and d. In some languages, what is typically spelled with an r is actually a flap. (But let's not get hung up on the spelling. What's important here is sounds, not letters. We have to use symbols to write down those sounds, but let's not lose sight of the fact that it's the sounds we're interested in.)

I said before that flapping—or To Flap or Not to Flap—was a matter of rule. Not a matter of whim, or laziness, or what have you. The reason we Americans flap isn't because we don't have the energy to pronounce everything written with a "t" in that very British aspirated form. We flap because that's just how American English works. (Hey, we also say [rather] instead of [rawther]—it's just part of what makes American English American English.) So what does the rule look like? It's simple:

When a t or d comes after a vowel and before an unstressed vowel, it becomes a flap.

(Okay, I lied. It's more complicated than this, but let's just go with this streamlined version.) The t in markets doesn't fit that pattern, so it doesn't get transformed into a flap. But the t in marketing does fit that pattern—it comes after a vowel and before an unstressed vowel—so it's transformed into a flap. Nothing could be simpler, once you've learned your language's system. Notice that a word like atomic is pronounced like [aTomic]. That's no flap in there, because the vowel that follows the t is stressed, so the flapping rule doesn't apply. The flapping rule does apply to atom, though, to give us [aDom]. (The same holds for the flap and nonflap in thirty and thirteen, respectively.) Potato has one aspirated t and one flap: [poTaDo]. Again, and I have to emphasize this, it's not a matter of laziness. In fact, in a sense, Americans are actually more concerned about such things than the British are. We go out of our way to include a rule about this in our language. We "care," linguistically speaking, about something some British English-speakers don't even think about. They don't flap. We do—but only sometimes, in these certain special cases. See? We need to be careful and make distinctions, where they just have a blanket policy.

What does it mean to say that flapping is a rule? It means that When To Flap (and What To Flap) can be found in the heads of every native American English-speaker. Oh sure, there might be some nonflappers hanging on for dear life, like maybe some so-called Boston Brahmins, but for the most part, flapping is everyday, garden-variety American English. There's nothing uneducated about it. It's not a Southern thing, or a Western thing, or a youth thing, or something engaged in by those lower socio-economic classes over there. And there are many, many such rules at work in our (and everyone else’s) language. Remember what I said about aspirated t vs. unaspirated t? That's a matter of a rule also. And the rule doesn't govern only t's, but also p's and k's. The rule, like most such rules, is pretty abstract. And it's something even very young English-speakers handle like pros. (The rule says something like: If a voiceless stop—the kind of sound that p, t, and k are—comes at the beginning of a word, or right before a stressed vowel, make it aspirated. Otherwise, don't bother.) It's because of this rule that we say pie with an aspirated p, but spy without one. Likewise, we pronounce akimbo with an aspirated k, and skit without one.

It might seem like this isn't actually a rule, but instead just a description of something we have to do. As though linguists just wrote down something natural and inevitable and said, "Behold the Rule of Aspiration!" After all, it's hard not to aspirate in those cases. It's hard to pronounce these words any differently. Try saying top without an aspirated t at the beginning. (It can even be hard for us to hear the difference!) Maybe this is because p's and t's and k's just automatically come out aspirated or unaspirated depending on what word they're in. Nope. Sounds reasonable, but that's wrong. Spanish-speakers and Korean-speakers, to name just two groups of many, don't feel compelled to aspirate all voiceless stops that come at the beginning of words. It's not that their mouths work differently; it's that they have learned a different set of rules. So you see, the idea that we carry around weird-looking rules in our heads isn't really all that strange, once you examine some of these rules and see what they might do.

Postlexical Rules

Back to flapping. What do linguists say about the flapping rule? How do they explain it, define it, describe it, and so on? Well, at least when I got my Master's in linguistics in the 90s, they called this rule a postlexical rule. It's not important right now why they called it that. What is important is what it means for a rule to be a postlexical rule. There are all sorts of phonological rules—rules that describe how we manipulate the symbols that stand for sounds. And I'm not talking about letters. Linguists are almost never interested in how we spell things. They're interested in how people represent language in their minds, whether they've ever learned to read and write or not. Like that rule above about aspiration. That rule involves all kinds of abstract, "technical" concepts like "voiceless stop"—which implies that speakers organize sounds into different categories—and "stressed vowel"—which suggests that we know the difference, on an abstract level, between stressed and unstressed vowels, and that the difference matters. And notice that the rule isn't a rule about t, or an unstressed a. It's a rule about general, abstract categories of things. This is what linguists believe our internal grammars—our symbolic representations of our language and the rules that govern it—actually look like. No, not with little t's written somewhere, not with anything written down, but rules do involve abstract representations of the features of language.

So what is a postlexical rule? A postlexical rule is a kind of phonological rule that operates across the board, with no exceptions, whenever and wherever it can. Any place the conditions for the rule are met, the rule applies. Between words, between roots and suffixes, within simple words... Postlexical rules don't care where they apply. In the case of flapping, this means that wherever the conditions of the rule are found (when a t or d comes after a vowel and before an unstressed vowel) the rule automatically applies and the t or d becomes a flap. There's no override switch, no “yes, but.” Inside a simple word like meteor—by simple, I mean that meteor is one single root, with no suffixes stuck onto it—the condition is found. (There's a t or d after a vowel and before an unstressed vowel.) And so what we write with a t in meteor is spoken as a flap: [meDeor]. The only place you'd expect to hear [meTeor]—with an aspirated t—is in England, or some other nonflapping region. Between a root like rocket and a suffix like the "-ed" that indicates past tense, the condition for flapping is found. That's why we say "the spaceship [rockeDed] across the galaxy," instead of [rockeTed]. And postlexical rules can even apply between words. Look at the sentence "Halley's comet is burning brightly." The conditions that trigger the flapping rule are here, too, and the rule doesn't care that part of the flap-trigger (the vowel and the t or d) is found in one word and another part of the flap-trigger (the following unstressed vowel) is found in another word. And so that sentence comes out "Halley's [comeD is] burning brightly" and not "Halley's [comeT is] burning brightly." Not all rules in English—or in other languages—work this way. Some rules never apply between words, and some rules never apply within simple words. Postlexical rules like the flap rule, though, will apply all over the place.

Note one consequence of flapping being classified as a postlexical rule: there won't be any words in American English that could have flaps in them, but don't. You won't find any words with aspirated t's where flaps would otherwise be expected. If it can flap, it will. Case closed. You won't find any place where the rule could apply, but where, for some reason, it doesn't.

(Of course, to be picky about it, it's not the classification of the rule that means there won't be exceptions; it's the lack of exceptions that leads to the classification of the rule. It's easy to start talking like the rules come first, but they don't. It's like the "law" of gravity. The law came after the facts, as an attempt to describe them, not the other way around. Even if Newton had never formulated the law of gravity in the first place, apples would still fall out of trees.)

It's very important that this point be understood: flapping or not flapping isn't a matter of the "correct" vs. "incorrect" use of language. Flapping is perfectly standard behavior for Americans. Everyone does it. Educated people, people in power, working people, people from all regions of the country and all walks of life. Professors flap, doctors flap, lawyers flap, CEOs flap, farmers flap. And not only is flapping utterly commonplace, it's also grammatical. That it is to say, it's systematic and rule-based. It's grammatical, in the sense that linguists use that term. It's a part of the language system we all learn and use, not something to be avoided or "hypercorrected" out of our mouths.

The Shame of It All

Here's an example of this kind of hyper-Briticism that Americans have been susceptible to for centuries: every year, if you listen for it, you'll hear some American sports commentator pronounce the name of a prestigious British tennis tournament wrong. You'll hear Wimbledon pronounced [wimbleTon], with an aspirated t where you'd expect a flap (or maybe a d). Where does this mispronunciation come from? We all make mistakes. We all have weird, idiosyncratic pronunciations in our heads, ready to leap out and brand us as mavericks. I don't think that's what's going on with "Wimbleton," though. What I think is going on is a reanalysis of the word on the part of a linguistically insecure announcer. Allow me to read his mind. He's thinking, "I know people usually pronounce that word [wimbleDon]. It looks like that flapping rule must have operated on the word. We Americans are so darn lazy and informal! We've corrupted another perfectly good British pronunciation and made ourselves look uneducated in the bargain. Well, I'll prove I'm an educated, sophisticated person: I'll pronounce the word as though that dirty old flapping rule had never applied to it. I'll say [wimbleTon], which is how I imagine it's really meant to be pronounced by the people who invented it!" So the poor fool bungles it and sounds worse than he would have if he had just been content with his humble linguistic heritage. (It was never [wimbleTon]—not even to the British!) No, I can't prove this is what's really going through people's minds when they come up with Wimbleton—and surely they're not aware of the rules they use—but it does fit nicely with our facts about phonological rules, and with what we've all seen of American English speakers' inferiority complex.

I remember a lowbrow example of this, too. Chris Elliott, in his brief but weird Fox sit-com Get a Life!, once cursed someone with the imprecation "Damn you to [haTes]" instead of [haDes], in a misguided attempt to appear sophisticated. (And, have you ever heard someone say, with a very formal tone, "[laTies] and gentlemen" instead of [laDies]? Again, same thing.)

The Telltale

So how do I know that NPR isn't just fancier than the rest of us? Heck, maybe all those commentators were brought up and educated in England, so that's why they talk the way they do. A reasonable hypothesis (sort of), but wrong. NPR is a hotbed of inconsistent nonflapping. It doesn't appear that there's a rule at work (such as "never flap" or "flap like normal"). There doesn't appear to be anything systematic about it at all. It's arbitrary. And this is what we'd expect from people who are winging it. Or putting on airs the best they can. Some flaps squeeze through, undetected. Let's face it—it's hard to notice all these things, and it can be exhausting trying to pay attention to them. This inconsistency is the telltale sign of affectation. The on-air personalities don't want to flap, as though there were something wrong with it, but they just can't help it sometimes.

My second hypothesis was that flapping, at least in the heads of NPR people, is no longer a postlexical rule. Perhaps the rule is becoming lexical—in other words, moving toward the level of individual words. (Lexical rules have exceptions, unlike postlexical rules.) Therefore, some words might have internal flapping, whereas others wouldn't. One thing derailing this hypothesis (besides the fact that I don't really understand it) is that NPR flapping often occurs between words (not the environment for lexical rules). It's almost as though NPR-speak favors the between-word environment for the application of the flapping rule. Again, this just sounds bizarre to me. It's like NPR invented a new category of phonological rule: the postpostlexical rule, or the cryptolexical rule, which applies ONLY between, and never within, words.

Of course, this isn't really a rule; it's just a tendency. (Perhaps it's easier to monitor our own within-word behavior, so it's easier to eradicate within-word flaps?) And on NPR some individual words have flaps sometimes, and aspirated t's other times. Even when spoken by the same person! Again, I conclude that this is a matter of affectation. Putting on airs. Carelessness in the attempt to sound more careful.

There also appears to be a sort of hyperaspiration at work here. It's not enough to fight unruly flaps wherever they appear—or wherever they're noticed. One must aspirate all t's. This leads to pronunciations like [waiT waiT, don'T tell me]. And it might, somehow, be responsible for one of KUOW's most annoying habits, referring to the station as "your news an dinformation station." Dinformation? It's as though every t or d must find its full expression! (I've even heard the word modern come out as [moTern] on NPR! Now you're refusing to flap d's and insisting on turning them into aspirated t's!)

Are there other examples of this Britishish speech at NPR? Well, yes, I can think of one. British English—at least the form of British English we Yankees think of as proper and high class—never has the [u] sound after the set of consonants known as coronals. So after n and t, for instance, you hear [yu] and not [u]. The word news gets pronounced [nyuz], instead of [nuz], and tune comes out [tyun]. NPR-speak employs this British-esque feature as well. And, again, it employs it inconsistently. Which is what drives me nuts.

Now, if you can bear a little more of my obsessive nonsense, I'd like to present some actual NPR data to you, to illustrate the preceding sermon.

The (old) Data

KUOW

12/18/2000

[waDer] as expected

[forDy] as expected

But: [concreT and waDer] (for concrete and water, where [concreD and waDer] would be expected)

KUOW

1/10/01

[forDy-eight] as expected

But: [forTy-five] where [forDy-five] expected

[uTiliTies] where [uTiliDies] is expected

[universiDy] as expected

NPR

1/22/01

[senaTor] alongside [democraDic]

NPR

2/20/01

[ciTy] alongside [ciDies]

KUOW

3/13/01

[staDe of the economy] and [universiDy of washington]

But: [staTe of washington] where [staDe of washington] is expected

KUOW

5/23/01

[universiDy of washington]

But: [social securiTy numbers]

NPR: "Wait, Wait! Don't Tell Me!"

7/14/01

[mathemaDical] as expected, alongside [activiTy]

NPR: "Marketplace"

8/17/01

[varieTy] alongside [varieDy]

NPR: "Wait, Wait! Don't Tell Me!"

9/8/01

[biTTen] (where you wouldn't expect aspiration or flapping!)

[manhatn] (as expected), but briTain (linguistic insecurity in action!)

[creaTed] and [relaTed] alongside [exciDed]

[noT officially over]

[marTin amis]

[starTed]

[auTomaTic] (two flaps that didn’t flap!)

KUOW

10/30/01

[vaniTy] alongside [mortaliDy]

KUOW

11/03/01

[compuTer] alongside [compuDer]

[thirTy] alongside [forDy]

Conclusion

Friday, April 10, 2015

My Love-Hate Relationship with Conlangs

Conlangs (constructed languages) are a mainstay of sci-fi and fantasy entertainment. The earliest conlanger most people (including me) have heard of is Ludwik Lazarus Zamenhof, the Polish doctor who gave Esperanto to the world in 1887. While not a sci-fi or fantasy author, he does seem to have believed some pretty fantastic things. Such as the utopian idea that having a language in common would keep humans from wanting to kill each other.

The most famous language inventor of all time is J. R. R. Tolkien, the creator of not only Bilbo, Frodo, and Gandalf, but also of Quenya and other languages. In fact, Tolkien himself has said that his first love was the languages he was creating. The stories were just excuses to use his inventions, to give them a place to live. (It was Tolkien's invented languages and words—so plausible, so real-sounding—that inspired and helped sustain my interest in linguistics when I was a teenager.)

I can't deny there's something inescapably silly about all the constructed languages littering the landscapes of fantasy and sci-fi literature and movies. And for every conlang made with care and an eye (and ear) toward believability and aesthetics, there are 730 (probably) that only make you cringe. From what I've seen, most conlangs look shoddy and unrealistic. I just don't buy them. And all that work—all that huffing and puffing—just to dress up some lamebrain costume drama! What a waste of imagination.

What appeals to me about inventing languages is not the idea that language shapes thoughts and that maybe with the "right" language we can mold the "right" thinking, or the hope that speaking this or that language can change the world, or the supposed majesty of fantasy franchises. I'm only in it for the words.

For me, an invented language of words that feel as real, as quintessentially themselves, as the lexicon of any natural language is—for reasons I've tried for a long time to understand—valuable. Such a system feels like a metaphor for language, a concept I just made up (and which I admit to not actually understanding). One thing I love about (natural) languages is their cohesiveness, the way they sound like themselves, the fact that their words all seem to have sprung from a single source, as though they share the same mysterious pedigree. Each one is a variation on one grand theme and has the authenticity that only a history of use can provide.

A conlang that mimics natural languages' suchness—presenting a refined, manageable simulacrum of reality—is as noble an artifact as any other work of art. Especially when you don't drag it through the mud of some epic realm or put it in the mouths of burly swordsmen or monsters from space. It's like a shadowbox or some finely wrought figure, a device that offers a glimpse of the lifelike, that evokes the Fascination of the Miniature. A created something that mirrors life so closely can have the power (somehow) to thrill and impress, beguile and please, even more than the natural. It gives us a way to take in the panorama in one glance, to enjoy a microcosm from our couches. And that's what's so compelling about conlangs, not all the dressing-up and monsters.

Full disclosure: I created the (not very extensive) version of the Sith language (Sith as in Star Wars? Darth Vader, Lord of the Sith?) that appears in Book of Sith (47North, 2012).

I like imagining those fictitious words—those unreal but realistic-enough-to-be-real words—in the mouths of gossips and poets, on billboards and street signs, on the radio and in newspaper headlines. All the places where real languages live. Give me a made-up language like that, as earthy and quirky and ingenious and ordinary as a real language, and I'll be happy.

When I look at a fantasy book—like, if I'm considering checking it out of the library for my son—the first thing I look at is the names of characters and (if there's a map) the countries and kingdoms. So often, the book loses me right there, at the names. I just don't believe that any parents anywhere—in the real world or in any imaginary one—would ever look at their newborn and, overcome with joy and hope, say, "I shall call him Brangbinax!" Sure, I made that example up, but it's no more unrealistic—no more untethered from the real word—than a million fantasy names I've seen before. Another way these books let me down is by diligently refusing to have any kind of consistent aesthetic, as though each name was conjured up by the characters from scratch, which isn't how we unmagic mortals usually do it. (Even novel names feel like they came from someplace. Because they do. We can usually place them within some larger societal scaffolding.) But a book with plausible names—names that just feel right, like they poured from some actual and particular wellspring of cultural genius—scores quick points with me.

The most famous language inventor of all time is J. R. R. Tolkien, the creator of not only Bilbo, Frodo, and Gandalf, but also of Quenya and other languages. In fact, Tolkien himself has said that his first love was the languages he was creating. The stories were just excuses to use his inventions, to give them a place to live. (It was Tolkien's invented languages and words—so plausible, so real-sounding—that inspired and helped sustain my interest in linguistics when I was a teenager.)

I can't deny there's something inescapably silly about all the constructed languages littering the landscapes of fantasy and sci-fi literature and movies. And for every conlang made with care and an eye (and ear) toward believability and aesthetics, there are 730 (probably) that only make you cringe. From what I've seen, most conlangs look shoddy and unrealistic. I just don't buy them. And all that work—all that huffing and puffing—just to dress up some lamebrain costume drama! What a waste of imagination.

What appeals to me about inventing languages is not the idea that language shapes thoughts and that maybe with the "right" language we can mold the "right" thinking, or the hope that speaking this or that language can change the world, or the supposed majesty of fantasy franchises. I'm only in it for the words.

For me, an invented language of words that feel as real, as quintessentially themselves, as the lexicon of any natural language is—for reasons I've tried for a long time to understand—valuable. Such a system feels like a metaphor for language, a concept I just made up (and which I admit to not actually understanding). One thing I love about (natural) languages is their cohesiveness, the way they sound like themselves, the fact that their words all seem to have sprung from a single source, as though they share the same mysterious pedigree. Each one is a variation on one grand theme and has the authenticity that only a history of use can provide.

A conlang that mimics natural languages' suchness—presenting a refined, manageable simulacrum of reality—is as noble an artifact as any other work of art. Especially when you don't drag it through the mud of some epic realm or put it in the mouths of burly swordsmen or monsters from space. It's like a shadowbox or some finely wrought figure, a device that offers a glimpse of the lifelike, that evokes the Fascination of the Miniature. A created something that mirrors life so closely can have the power (somehow) to thrill and impress, beguile and please, even more than the natural. It gives us a way to take in the panorama in one glance, to enjoy a microcosm from our couches. And that's what's so compelling about conlangs, not all the dressing-up and monsters.

Full disclosure: I created the (not very extensive) version of the Sith language (Sith as in Star Wars? Darth Vader, Lord of the Sith?) that appears in Book of Sith (47North, 2012).

I like imagining those fictitious words—those unreal but realistic-enough-to-be-real words—in the mouths of gossips and poets, on billboards and street signs, on the radio and in newspaper headlines. All the places where real languages live. Give me a made-up language like that, as earthy and quirky and ingenious and ordinary as a real language, and I'll be happy.

When I look at a fantasy book—like, if I'm considering checking it out of the library for my son—the first thing I look at is the names of characters and (if there's a map) the countries and kingdoms. So often, the book loses me right there, at the names. I just don't believe that any parents anywhere—in the real world or in any imaginary one—would ever look at their newborn and, overcome with joy and hope, say, "I shall call him Brangbinax!" Sure, I made that example up, but it's no more unrealistic—no more untethered from the real word—than a million fantasy names I've seen before. Another way these books let me down is by diligently refusing to have any kind of consistent aesthetic, as though each name was conjured up by the characters from scratch, which isn't how we unmagic mortals usually do it. (Even novel names feel like they came from someplace. Because they do. We can usually place them within some larger societal scaffolding.) But a book with plausible names—names that just feel right, like they poured from some actual and particular wellspring of cultural genius—scores quick points with me.

Korean as Mirror English

Because of deep differences in the way Korean and English handle fundamental units of syntax—how the languages structure and order phrases—they sometimes appear like mirror images of each other. From my perspective, everything in Korean is backwards!

Take a straightforward sentence like this:

"I saw the tree in the vicinity of the library."

In Korean, this could be translated like so:

나는 도서관의 근처에 나무를 봤어요.

Reading from the beginning, one word at a time, you get:

"I / library's / vicinity-in / tree / saw."

But flip it around and read from the end of this sentence to the beginning, and you get:

"Saw / tree / in vicinity / of library / I."

If you ignore the fact that Korean doesn't have articles like English does and that both English and Korean typically stick their subjects at the beginning of the sentence (when Korean actually uses a subject), you see that structurally Korean and English are like opposites. The ways they string together their word groupings are reversed.

Sometimes, when I'm having trouble translating a tough (or not-so-tough) sentence, my teacher will have me start from the end and work my way to the front. In this way—once I've interpreted it the way no one could ever interpret a spoken sentence—it all makes sense.

Take a straightforward sentence like this:

"I saw the tree in the vicinity of the library."

In Korean, this could be translated like so:

나는 도서관의 근처에 나무를 봤어요.

Reading from the beginning, one word at a time, you get:

"I / library's / vicinity-in / tree / saw."

But flip it around and read from the end of this sentence to the beginning, and you get:

"Saw / tree / in vicinity / of library / I."

If you ignore the fact that Korean doesn't have articles like English does and that both English and Korean typically stick their subjects at the beginning of the sentence (when Korean actually uses a subject), you see that structurally Korean and English are like opposites. The ways they string together their word groupings are reversed.

Sometimes, when I'm having trouble translating a tough (or not-so-tough) sentence, my teacher will have me start from the end and work my way to the front. In this way—once I've interpreted it the way no one could ever interpret a spoken sentence—it all makes sense.

The Joy of Languages Being Themselves

Imagine a language's lexicon—all the words it contains—as a machine that spits out well-formed words.

Inside that word machine are all kinds of gears and flanges (?) and... manifolds (??) that determine the nature of the words that are spat out. They limit the sounds that are used and the various ways those sounds can be combined.

When you turn the crank on the English word machine, you get English words. But you get more than that: you also get possible English words. So you get pancake, ridiculous, and grumble and also English words that don't exist, but could.

What are examples of English words that could exist but happen not to? How about: potcake, ridiculish, and glumble (to mutter glumly, maybe). Beyond that—beyond these not-real-but-plausible words we can easily imagine and even concoct meanings for—are the truly imaginary words that don't come ready-made with connotations and possible references. Words like merb, channitude, and frift.

I claim that these are all English words. They're just English words that don't (yet?) mean anything. It's very possible no one has ever spoken them. But if someone swore that those were actual words—in the dictionary and everything!—you'd probably believe it and tell the person to calm down already. There's nothing un-English about merb or channitude. And there are regular English words that look very similar to frift. Namely, drift, grift, thrift, lift. The only reason we know (or suspect) that those aren't real words is that we've never heard them. But there are tons of English words in good standing that we've never heard. This is the basis of the game Balderdash, after all. Dictionaries are full of words no one has actually said in a hundred years.

But what if I told you that fnolr, zboshm, and glal were words? Sure, they look like I tossed a handful of Scrabble tiles onto the floor, but what if?

And what if I told you that kto, pferd, and wa'a were words? You'd probably be so sick of the whole thing you'd storm out of the room.

The moment of truth:

The first set is, of course, dumb-looking gibberish. But the second set are all words, just not English words. Kto is Russian for "who," Pferd is German for "horse," and wa'a is Hawaiian for "canoe." The boxes that produced those words have different guts from the guts of the English box, but in their languages, those words are every bit as well-formed and lived-in as pancake.

It's hard (impossible, maybe) to do it for your own language, but have you ever given thought to what words are, somehow, perfect examples of Russianness or Spanishness or Japaneseness? I think about this with relation to Korean all the time. I'll learn a new word and think, "That is just so Korean" (whatever that means). 해변 (haebyeon "beach"), 별 (pyeol "star"), and 감자 (kamja "potato") couldn't be anything but Korean, such perfect exemplars they are of what makes something sound like Korean. If they weren't actual Korean words, they could be. If they weren't real words, I can only assume Koreans would believe they were real—just not yet known to them—or at least could be, the same way English speakers wouldn't have too much trouble accepting that crat, horm, and fellish just might be real words whose acquaintance they haven't yet made.

Inside that word machine are all kinds of gears and flanges (?) and... manifolds (??) that determine the nature of the words that are spat out. They limit the sounds that are used and the various ways those sounds can be combined.

When you turn the crank on the English word machine, you get English words. But you get more than that: you also get possible English words. So you get pancake, ridiculous, and grumble and also English words that don't exist, but could.

What are examples of English words that could exist but happen not to? How about: potcake, ridiculish, and glumble (to mutter glumly, maybe). Beyond that—beyond these not-real-but-plausible words we can easily imagine and even concoct meanings for—are the truly imaginary words that don't come ready-made with connotations and possible references. Words like merb, channitude, and frift.

I claim that these are all English words. They're just English words that don't (yet?) mean anything. It's very possible no one has ever spoken them. But if someone swore that those were actual words—in the dictionary and everything!—you'd probably believe it and tell the person to calm down already. There's nothing un-English about merb or channitude. And there are regular English words that look very similar to frift. Namely, drift, grift, thrift, lift. The only reason we know (or suspect) that those aren't real words is that we've never heard them. But there are tons of English words in good standing that we've never heard. This is the basis of the game Balderdash, after all. Dictionaries are full of words no one has actually said in a hundred years.

But what if I told you that fnolr, zboshm, and glal were words? Sure, they look like I tossed a handful of Scrabble tiles onto the floor, but what if?

And what if I told you that kto, pferd, and wa'a were words? You'd probably be so sick of the whole thing you'd storm out of the room.

The moment of truth:

The first set is, of course, dumb-looking gibberish. But the second set are all words, just not English words. Kto is Russian for "who," Pferd is German for "horse," and wa'a is Hawaiian for "canoe." The boxes that produced those words have different guts from the guts of the English box, but in their languages, those words are every bit as well-formed and lived-in as pancake.

It's hard (impossible, maybe) to do it for your own language, but have you ever given thought to what words are, somehow, perfect examples of Russianness or Spanishness or Japaneseness? I think about this with relation to Korean all the time. I'll learn a new word and think, "That is just so Korean" (whatever that means). 해변 (haebyeon "beach"), 별 (pyeol "star"), and 감자 (kamja "potato") couldn't be anything but Korean, such perfect exemplars they are of what makes something sound like Korean. If they weren't actual Korean words, they could be. If they weren't real words, I can only assume Koreans would believe they were real—just not yet known to them—or at least could be, the same way English speakers wouldn't have too much trouble accepting that crat, horm, and fellish just might be real words whose acquaintance they haven't yet made.

Korean Mnemonics 1: putting in and putting on

Learning new vocabulary in a foreign language is a never-ending struggle. It often feels like I've filled up every available space already, so when I try to learn a new batch of words they just overflow the tank and slosh over the sides and down the drain. So any little trick helps. Here's how my teacher helped me learn to remember the differences among three very similar-looking words.

1. 넣다 2. 놓다 3. 낳다

1. neohta 2. nohta 3. nahta

They're almost the same, the only difference being in the first vowel: ㅓ, ㅗ, or ㅏ.

And what's worse, 1. and 2. mean very similar things, too.

1. neohta means "put in," 2. nohta means "put on," and 3. nahta means "give birth." What's the trick? The shapes of those vowels are like little pictures: The ㅓ of 넣다 is going into the ㄴ. See it tucked into the crook of the ㄴ's elbow?

The ㅗ of 놓다 is lying flat on top of the ㅎ. Picture the top of a cookie jar or the lid of a pot resting on a countertop.

And in the ㅏof 낳다, you see a little line coming out of the big line.

These pictures tell the stories of the verbs' meanings: put in, put on, and give birth (something comes out).

Ingenious.

Three verbs down, seven million to go.

1. 넣다 2. 놓다 3. 낳다

1. neohta 2. nohta 3. nahta

They're almost the same, the only difference being in the first vowel: ㅓ, ㅗ, or ㅏ.

And what's worse, 1. and 2. mean very similar things, too.

1. neohta means "put in," 2. nohta means "put on," and 3. nahta means "give birth." What's the trick? The shapes of those vowels are like little pictures: The ㅓ of 넣다 is going into the ㄴ. See it tucked into the crook of the ㄴ's elbow?

The ㅗ of 놓다 is lying flat on top of the ㅎ. Picture the top of a cookie jar or the lid of a pot resting on a countertop.

And in the ㅏof 낳다, you see a little line coming out of the big line.

These pictures tell the stories of the verbs' meanings: put in, put on, and give birth (something comes out).

Ingenious.

Three verbs down, seven million to go.

Ergatives in English: grammatical dinosaurs?

English is full of ergative verbs—verbs whose semantic objects appear as their subjects:

For those of you who've forgotten, or who never knew (or who never cared), transitive verbs are verbs that take objects. That is, they name actions that happen to something or someone. Destroy is a transitive verb because when it shows up, the thing destroyed also has to be mentioned. "The marauders destroyed the farming village" is a fine sentence, but "The marauders destroyed" isn't. It's lopsided. It leaves us hanging, just waiting. "Yes? They destroyed... what?" English speakers know that the object just has to be there. (Not all English speakers know the terms transitive and object, of course, but they understand the concepts, and they know which verbs are—or can be—transitive and (at least sometimes) require objects. Which is why "The marauders destroyed" sounds weird to English speakers.)

What's interesting is that the grammatical subjects of those verbs—the door, the cookie, and the glass—are the objects of the actions. The door didn't slam something shut; it was slammed shut. The cookie didn't crumble something; it got crumbled. And the glass didn't break anything; it was broken. In these sentences, semantic objects show up as grammatical subjects. By the way, English isn't alone in using this kind of construction, called the ergative.

You see it in sentences like these too:

"There used to be a stupid advertising slogan about 'the soup that eats like a meal,'" I told him.

He was unimpressed, and he held his ground. "Kids do not say stuff like that!"

Is he right? And if so, what does that mean? Does it mean ergatives are on the way out? In 50 years, will sentences like those noted above (or even ones like "The new Claude Clodworthy novel is a turgid read"—suggesting to the linguistically naive that the novel reads something, instead of being something people read) sound hopelessly obsolete? Are ergatives going the way of whom?

Or are ergatives just not part of kids' linguistic arsenal? (Kids don't say notwithstanding or fiduciary too often either, but we don't take that as evidence that those grown-up words are on their last legs.) Maybe English speakers just have to grow into ergatives the same way people have to grow into calculus and a nuanced appreciation of Claude Clodworthy.

Or maybe the kid is just full of it.

- The door slammed shut.

- That's the way the cookie crumbles.

- The cat knocked the glass off the table and it broke.

For those of you who've forgotten, or who never knew (or who never cared), transitive verbs are verbs that take objects. That is, they name actions that happen to something or someone. Destroy is a transitive verb because when it shows up, the thing destroyed also has to be mentioned. "The marauders destroyed the farming village" is a fine sentence, but "The marauders destroyed" isn't. It's lopsided. It leaves us hanging, just waiting. "Yes? They destroyed... what?" English speakers know that the object just has to be there. (Not all English speakers know the terms transitive and object, of course, but they understand the concepts, and they know which verbs are—or can be—transitive and (at least sometimes) require objects. Which is why "The marauders destroyed" sounds weird to English speakers.)

What's interesting is that the grammatical subjects of those verbs—the door, the cookie, and the glass—are the objects of the actions. The door didn't slam something shut; it was slammed shut. The cookie didn't crumble something; it got crumbled. And the glass didn't break anything; it was broken. In these sentences, semantic objects show up as grammatical subjects. By the way, English isn't alone in using this kind of construction, called the ergative.

You see it in sentences like these too:

- Sure, the car's got more than 300,000 miles on her, but she handles like a dream. (The car is the thing being handled, not the thing handling something else.)

- You're wasting your time, Bruno. That safe won't crack without dynamite. (The safe is the thing being—or not being—cracked, not the thing cracking something else.)

- This bushel of kale will cook up nicely. (The kale is the stuff being cooked, not the thing cooking something else.)

- My grandma was a tough old thing who didn't scare easily. (It's not that she has a hard time scaring people—it's not easy to scare her.)

- After lots of huffing and puffing, the Big Bad Wolf knew the brick house just wouldn't blow down. (You get it.)

- A watched pot never boils.

- That paper cut will heal in no time.

"There used to be a stupid advertising slogan about 'the soup that eats like a meal,'" I told him.

He was unimpressed, and he held his ground. "Kids do not say stuff like that!"

Is he right? And if so, what does that mean? Does it mean ergatives are on the way out? In 50 years, will sentences like those noted above (or even ones like "The new Claude Clodworthy novel is a turgid read"—suggesting to the linguistically naive that the novel reads something, instead of being something people read) sound hopelessly obsolete? Are ergatives going the way of whom?

Or are ergatives just not part of kids' linguistic arsenal? (Kids don't say notwithstanding or fiduciary too often either, but we don't take that as evidence that those grown-up words are on their last legs.) Maybe English speakers just have to grow into ergatives the same way people have to grow into calculus and a nuanced appreciation of Claude Clodworthy.

Or maybe the kid is just full of it.

Favorite Words 1: English

I don't know if they're really favorites, but these are all words I love. I'm not talking about words I'm supposed to love because of what they mean. ("The most beautiful words in the English language are hope and love." Barf.) Or words I'm supposed to love because they have a supposedly universal appeal, like liquid or the unaccountably famous cellar door. I mean words that just push all the right buttons inside my ears. You have ear buttons, too, don't you?

I don't think I've ever heard anyone use these, except maybe anhinga, used when pointing at an anhinga, I'm guessing. Most of them aren't going to come up in casual conversation. Unless you're a volcanologist or a kidney specialist or some kind of weirdo.

You know, it occurs to me that none of these English words is really all that Englishy. They're New Latin or of otherwise foreign provenance. Maybe the next post about favorite English words will feature words of a more earthy Englishness.

(You can adopt a favorite word at http://www.adoptaword.com/ to benefit I CAN, "the children's communication charity" and all the people they benefit.)

- lithotripter (a device that breaks up kidney stones)

- anhinga (Anhinga anhinga, also called the snakebird)

- tephra (rocks and other solids ejected from volcanoes)

- limulus (genus of horseshoe crabs and stuff)

- clinquant (glittering)

- pipsissewa (an evergreen of the genus Chimaphila, especially C. umbellata)

I don't think I've ever heard anyone use these, except maybe anhinga, used when pointing at an anhinga, I'm guessing. Most of them aren't going to come up in casual conversation. Unless you're a volcanologist or a kidney specialist or some kind of weirdo.

You know, it occurs to me that none of these English words is really all that Englishy. They're New Latin or of otherwise foreign provenance. Maybe the next post about favorite English words will feature words of a more earthy Englishness.

(You can adopt a favorite word at http://www.adoptaword.com/ to benefit I CAN, "the children's communication charity" and all the people they benefit.)

On Fake Latin Plurals

There's something about Latin. To English speakers, at least, Latin occupies a position of unimpeachable authority. Latin has come to represent an ideal of logic and rigor, which is kind of dumb. Because, like plebeian languages—like English, say—Latin was a regular language spoken by regular people. Two thousand years ago the language that would one day bewilder and bedevil schoolchildren in Europe and America was used to argue, complain, haggle, seduce, insult, cajole, and amuse. It wasn't reserved for orators, philosophers, and emperors but lived instead in the mouths and ears of ordinary people who were basically the same as you and me, the same as people in all times and places have been.

It might be this near-reverence for Latin that causes people to reach a bit and adopt plural forms that don't make any sense in English but that look Latinish. If they have the look of Latin, they might lend a little of Latin's polish and gravitas. Which might be why some people pronounce the plurals of bias and process as "biaseez" and "processeez." There are Latin (and Greek) plurals that work this way, and they can be found in English words ending in -is—like thesis and crisis—that were borrowed whole from Latin and Greek.

Another kind of fake Latin plural is the very common octopi. Octopus looks like one of those ends-in-us words that get -i plurals (words like alumnus), so it's only fair, I guess, that people really, really want to give it a Latinate plural. Never mind that it's not a Latin word. It's an English word built in the 1700s from Greek roots. The "real" Greek plural would be octopodes, which is ridiculous for an English word. Me, I prefer octopuses, which happens to be what dictionaries prefer, too. For whatever that's worth.

Bonus observation: Most English speakers only imperfectly understand Latin and Ancient Greek noun declensions (surprise!), which is why they use criteria and phenomena as singular forms.

Update (6/16/15): Today, I heard someone on NPR use phenomenon as a plural. It's chaos out there. Be careful.

It might be this near-reverence for Latin that causes people to reach a bit and adopt plural forms that don't make any sense in English but that look Latinish. If they have the look of Latin, they might lend a little of Latin's polish and gravitas. Which might be why some people pronounce the plurals of bias and process as "biaseez" and "processeez." There are Latin (and Greek) plurals that work this way, and they can be found in English words ending in -is—like thesis and crisis—that were borrowed whole from Latin and Greek.

Another kind of fake Latin plural is the very common octopi. Octopus looks like one of those ends-in-us words that get -i plurals (words like alumnus), so it's only fair, I guess, that people really, really want to give it a Latinate plural. Never mind that it's not a Latin word. It's an English word built in the 1700s from Greek roots. The "real" Greek plural would be octopodes, which is ridiculous for an English word. Me, I prefer octopuses, which happens to be what dictionaries prefer, too. For whatever that's worth.

Bonus observation: Most English speakers only imperfectly understand Latin and Ancient Greek noun declensions (surprise!), which is why they use criteria and phenomena as singular forms.

Update (6/16/15): Today, I heard someone on NPR use phenomenon as a plural. It's chaos out there. Be careful.

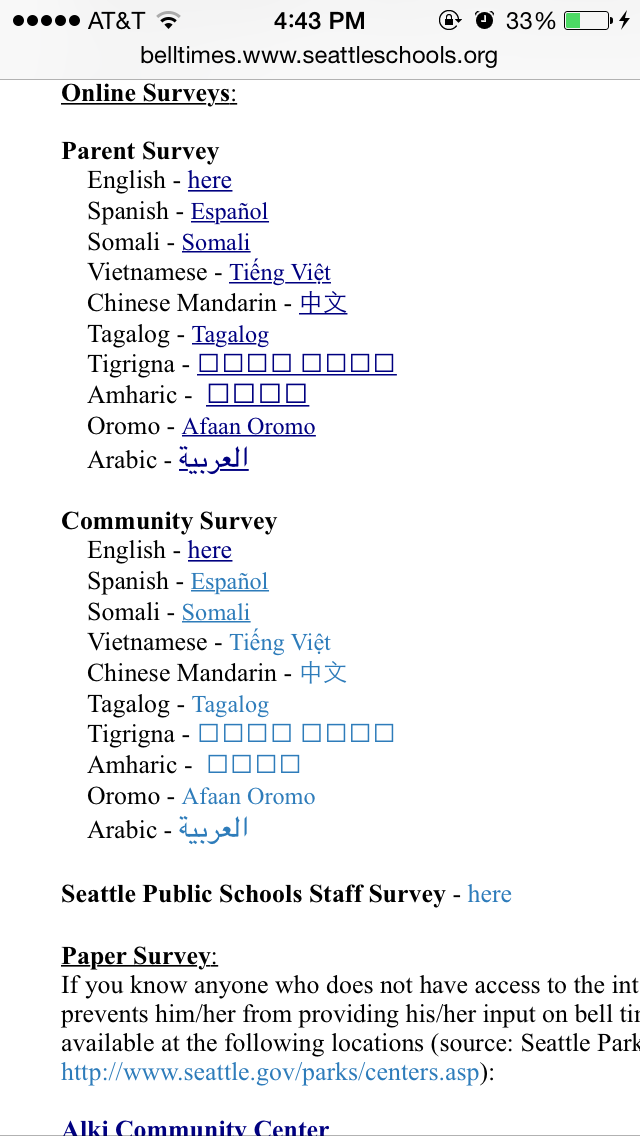

Roll on, Bureaucracy

This has always confused me: On some government forms, when they use

different languages, the name of each language is printed in English.

So, above the paragraph written in Chinese, for instance, it says Chinese—in English. And above the paragraph in Spanish, it says Spanish in English. But why? If you're looking at the Chinese paragraph, don't

you know that it's Chinese, especially if you speak Chinese? (If you don't speak Chinese, what difference does it make to you that that unintelligible paragraph is written in Chinese and not Armenian?) If you're

looking at the Spanish, you know that it's Spanish. It doesn't have to

say that it's Spanish. And if it did have to say that, it wouldn't have

to say it in English.

So who are these labels for? And who decided they needed to be there?

I don't think it's a simple, economical way to help government workers identify foreign languages. Or... maybe it is. Maybe if all of the languages are labeled in English then people who speak only English know how to find the right forms for a given situation? But usually when I see this phenomenon—as on this page of a form I received in the mail today, with Korean, Laotian, and Russian instructions—there's a whole bunch of languages listed, and not just one.

Here's a slight variation I spotted while researching health insurance plans:

In this version, at least the names of the languages appear in those languages, albeit after the superfluous English names.

I'm going to file this one under Mystery: unsolved.

Addendum: After writing this post, more of these things have surfaced. Now I see them everywhere. In figure 3, the name of the language appears—bolded and in English—after the text. Which seems pretty unreasonable to me. And in figure 4, well... Just look.

Now comes figure 5, from a beach in Bellingham, Washington. The breadth of Asian languages represented is impressive. But... why English labels, again?

So who are these labels for? And who decided they needed to be there?

I don't think it's a simple, economical way to help government workers identify foreign languages. Or... maybe it is. Maybe if all of the languages are labeled in English then people who speak only English know how to find the right forms for a given situation? But usually when I see this phenomenon—as on this page of a form I received in the mail today, with Korean, Laotian, and Russian instructions—there's a whole bunch of languages listed, and not just one.

Here's a slight variation I spotted while researching health insurance plans:

In this version, at least the names of the languages appear in those languages, albeit after the superfluous English names.

I'm going to file this one under Mystery: unsolved.

Addendum: After writing this post, more of these things have surfaced. Now I see them everywhere. In figure 3, the name of the language appears—bolded and in English—after the text. Which seems pretty unreasonable to me. And in figure 4, well... Just look.

|

| Fig. 4 |

|

| Fig. 3 |

Now comes figure 5, from a beach in Bellingham, Washington. The breadth of Asian languages represented is impressive. But... why English labels, again?

|

| Fig. 5 |

Learning Korean 1

I've been learning Korean since September 2013. At my first teacher's recommendation, I started using the You Speak Korean! series of books by Soohee Kim, Emily Curtis, and Haewon Cho. I'm currently on book 3, Intermediate Korean 1. My second (and current) teacher even helped with the creation of the series.

I'd studied plenty of languages before Korean (Latin, Russian, Ancient Greek, German, Old English, Sanskrit, and Finnish), but with Korean it's completely different. For one thing, I'm not enrolled in college or grad school this time around. In other words, I'm old. My efforts feel much more deliberate now, more self-directed. And I take a much more active approach to language learning than I ever did before. I do exercises in my book, and I write sentences to practice and showcase points of grammar as I learn them. But I also listen to podcasts about learning Korean. Every week, I go to a meetup of English speakers learning Korean and Koreans learning English. I get together with a Korean friend for chatting and help. I watch (subtitled) Korean dramas. I compose sentences in my head all the time. I look up words. My engagement with Korean is so much richer than my engagement with Russian, say, ever was. (Although I sometimes think my Russian fluency, at its peak, was better than my current Korean fluency.) Part of that is the changing times. In the mid-80s, I couldn't access the same breadth of pop culture, and so on. No one could. Before the Internet, finding kindred spirits and this kind of language material was impossible.

And unlike Latin or Sanskrit, Korean is alive and well. So I can encounter it in a wide variety of contexts and settings. Pop songs, websites, overheard conversations. This means my experience with it, active and passive, is so much more real than it could ever be with half the languages I've studied. So, while I use a textbook and work with a tutor and think about things the way someone with a linguistics background might, my experience with Korean isn't merely academic. It exists in the world of, you know, people.

Still, I've never lived in Korea. And I'm too bashful to throw myself into Korean-speaking opportunities with abandon. And, like I said, my brain is getting old, well past the point where absorbing a new language is merely a matter of exposure.

I'd studied plenty of languages before Korean (Latin, Russian, Ancient Greek, German, Old English, Sanskrit, and Finnish), but with Korean it's completely different. For one thing, I'm not enrolled in college or grad school this time around. In other words, I'm old. My efforts feel much more deliberate now, more self-directed. And I take a much more active approach to language learning than I ever did before. I do exercises in my book, and I write sentences to practice and showcase points of grammar as I learn them. But I also listen to podcasts about learning Korean. Every week, I go to a meetup of English speakers learning Korean and Koreans learning English. I get together with a Korean friend for chatting and help. I watch (subtitled) Korean dramas. I compose sentences in my head all the time. I look up words. My engagement with Korean is so much richer than my engagement with Russian, say, ever was. (Although I sometimes think my Russian fluency, at its peak, was better than my current Korean fluency.) Part of that is the changing times. In the mid-80s, I couldn't access the same breadth of pop culture, and so on. No one could. Before the Internet, finding kindred spirits and this kind of language material was impossible.

And unlike Latin or Sanskrit, Korean is alive and well. So I can encounter it in a wide variety of contexts and settings. Pop songs, websites, overheard conversations. This means my experience with it, active and passive, is so much more real than it could ever be with half the languages I've studied. So, while I use a textbook and work with a tutor and think about things the way someone with a linguistics background might, my experience with Korean isn't merely academic. It exists in the world of, you know, people.

Still, I've never lived in Korea. And I'm too bashful to throw myself into Korean-speaking opportunities with abandon. And, like I said, my brain is getting old, well past the point where absorbing a new language is merely a matter of exposure.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)